WHAT WE DO

We try to make lives and the environment better with science and design. We focus on incentives, outcomes, and sustainability.

Our foundation is science, yet we work and collaborate outside of science to design and implement solutions and ventures. We try hard to work across sectors to integrate behavioral science, finance, human-centered design, markets, natural science, and technology to solve problems.

Much of our work involves program design, sustainability science, and evaluation.

We don’t always succeed. But, we always learn.

Program Design

We combine science and human-centered design to create new ways of approaching environmental problem solving.

Sustainability Science

We conduct synthetic science to inform environmental conservation and sustainability decision-making.

Evaluation

We collaborate with foundations and others to monitor, evaluate, and learn from existing environmental efforts and programs.

WHAT WE'RE DOING

- All

- At-risk Species

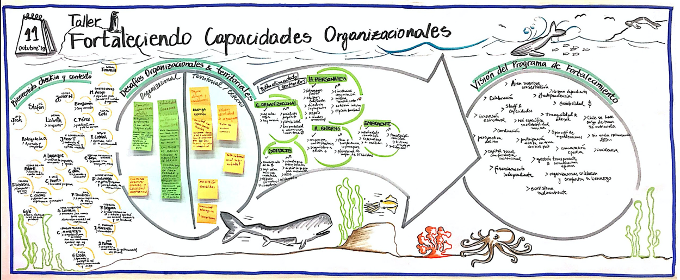

- Capacity Building & Shorebirds

- Evaluation

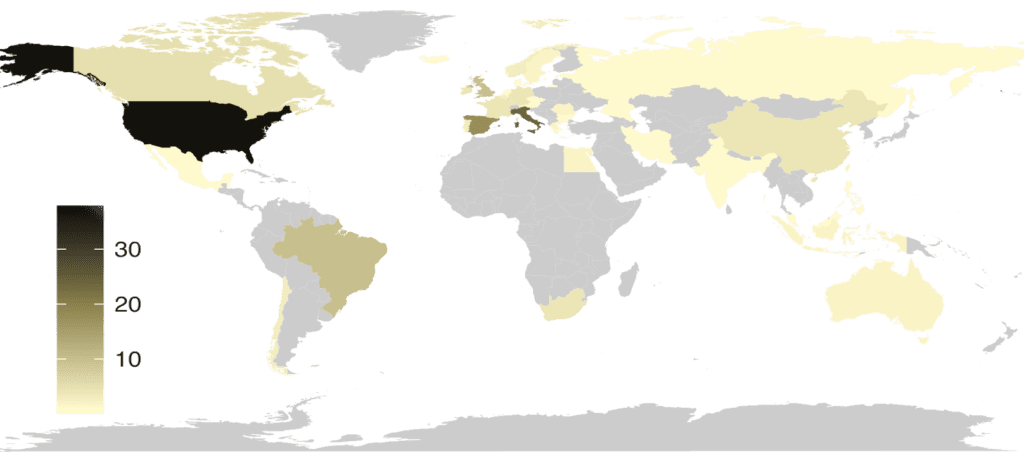

- Illegal Fisheries

- MEL & Marine Conservation in Chile

- Program Design

- Seafood Mislabeling

- Sustainability Science